An overview of systems engineering core concepts

Recently, I wrote about my process for using an LLM as a personal tutor for the Introduction to Systems Engineering course I am taking. This post is a direct result of that process. I have synthesised the core concepts from the first half of the course into a single overview. My goal is to solidify my own understanding and share a clear, practical summary of the foundational principles of systems engineering. I hope it also encourages you to explore the course yourself. There is much extra detail and insight in the course itself; it is an excellent course for anyone working with complex systems.

This is a longer post, but I have structured it to be as scannable as possible, covering the journey from defining a system to engineering its requirements.

What is a system?

The course starts with the most fundamental question. In systems engineering, a system is defined as a set of elements that interact to achieve a stated purpose. This simple definition forces us to be precise about three things: the system’s elements, their interconnections, and its mission.

A key concept here is the system boundary, which defines what is inside our ‘System of Interest’ and what is in the external environment. This boundary determines the project’s scope and clarifies our responsibilities.

The system life cycle

Every system, from a simple application to a complex aircraft, goes through a life cycle. Understanding these phases is essential because decisions made in one phase have consequences in all others. The generic life cycle has four major phases:

- Pre-Acquisition: The conceptual phase where the business need is identified, a business case is developed, and feasibility is assessed.

- Acquisition: The phase where the system is designed, built, and tested. This is the heart of the engineering effort.

- Utilization: The operational phase where the system is used and supported. This is typically the longest and most expensive phase.

- Retirement: The final phase where the system is disposed of at the end of its useful life.

The acquisition phase itself is broken down into four sequential activities, each ending with a critical review that establishes a design ‘baseline’.

| Activity | Review | Baseline Established | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conceptual Design | System Design Review (SDR) | Functional Baseline | Defines what the system must do (the logical architecture). |

| Preliminary Design | Preliminary Design Review (PDR) | Allocated Baseline | Maps the ‘what’ to a high-level ‘how’ (subsystem design). |

| Detailed Design | Critical Design Review (CDR) | Product Baseline | Details the design down to the component level for manufacturing. |

| Construction | Formal Qualification Review (FQR) | Qualified System | The system is built, tested, and accepted for use. |

Each baseline represents an increasing level of detail and a decreasing flexibility to make changes. This structured approach helps prevent costly errors late in the process.

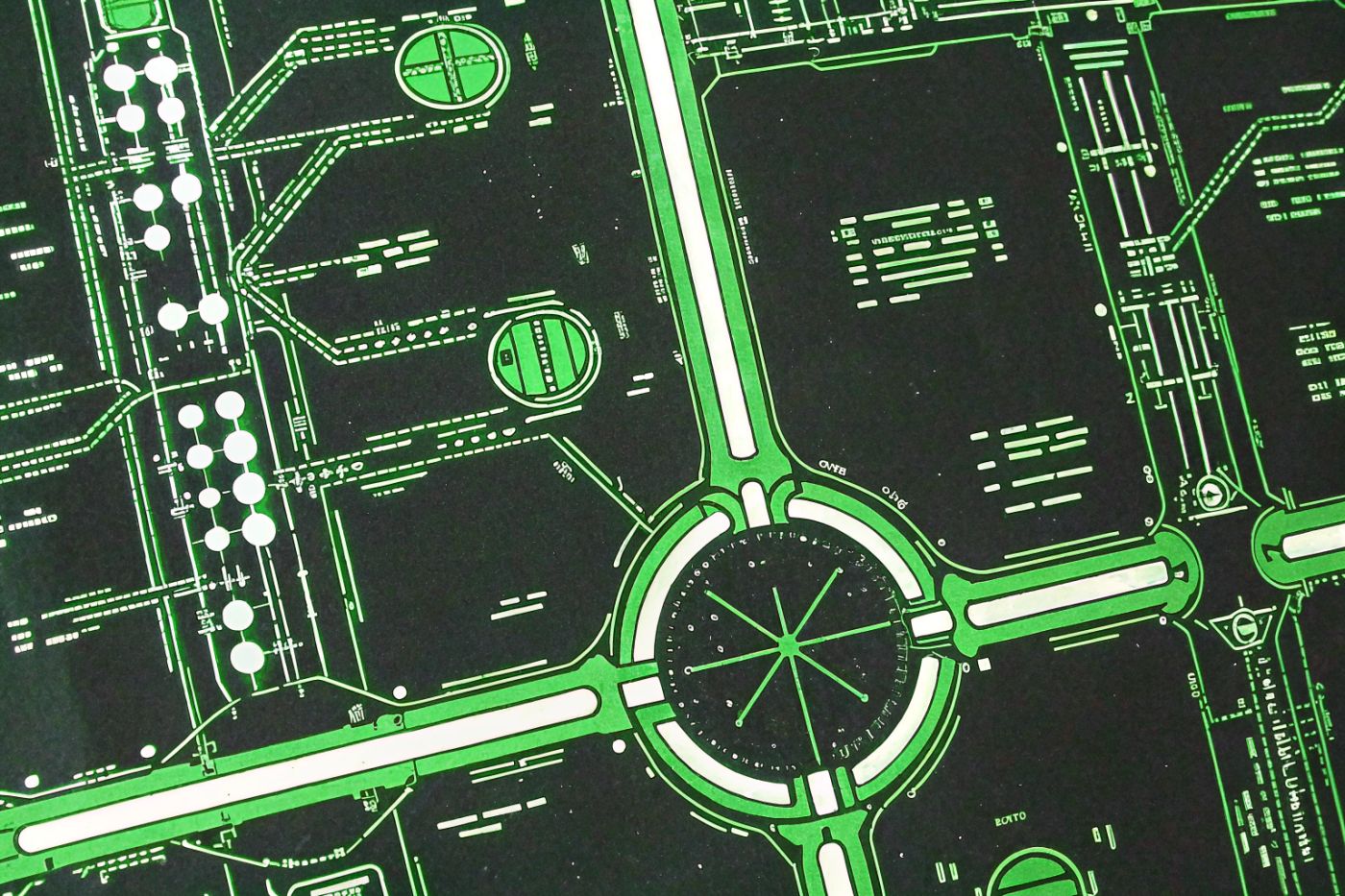

The two views: logical versus physical

A core principle is the separation of the logical and physical architecture.

- Logical Architecture (The “What”): Describes what the system will do, how well it will perform, and under what conditions. It is based on requirements and is relatively stable over time. The purpose of an engine—to provide motion—has not changed much, even as the technology has.

- Physical Architecture (The “How”): Describes the actual components, how they are manufactured, and how they are integrated. This is based on design specifications and changes rapidly with technology.

We always develop the logical architecture first. Understanding the problem clearly before committing to a specific solution prevents us from being constrained by old technology or legacy thinking.

The discipline of systems engineering

With the foundations in place, the course defines what systems engineering actually is. It is not about a specific engineering field but a holistic discipline focused on six key areas:

- Requirements engineering: Systematically managing stakeholder needs.

- A top-down approach: Starting at the system level and decomposing downwards.

- A life cycle perspective: Considering all phases from concept to retirement.

- System optimisation and balance: Making the whole system work well, not just the parts.

- Integration of disciplines: Coordinating various engineering specialities.

- Management: A structured process for managing complexity.

Without this discipline, it is easy to create systems that are functional but unnecessarily complex, like the famous Rube Goldberg machines.

The fundamental process used throughout is Analysis-Synthesis-Evaluation (A-S-E). It is an iterative loop: we analyse the problem, synthesise potential solutions, and evaluate them against the requirements. This loop is repeated at every level of design, from the overall system down to the smallest component.

A common misconception is that systems engineering adds cost. In reality, it shifts costs. By investing more effort upfront in requirements and design (the A-S-E process), we significantly reduce expensive changes and rework during construction and operation, leading to a lower total life cycle cost.

The language of needs and requirements

The language of systems engineering is built on a clear distinction between needs and requirements.

- Needs are expectations from the business or stakeholders, stated in their language. For example, “I need a secure place to park my car.”

- Requirements are formal, agreed-upon obligations derived from those needs. They are precise and, crucially, verifiable. For example, “The system shall include a garage with a lockable door.”

This transformation from abstract needs to concrete requirements happens in a structured hierarchy, often captured in a series of documents:

- Concept of Operations (ConOps): The high-level vision of how the system will be used.

- Business Requirements Specification (BRS): Formalises the business needs.

- Stakeholder Requirements Specification (StRS): Formalises the needs of users and other stakeholders.

- System Requirements Specification (SyRS): The technical specification that the developers will build against.

A well-formed requirement is necessary, unambiguous, feasible, and verifiable. If you cannot define how to test a requirement, it is probably not a good requirement.

The process of requirements engineering

The formal process for defining and managing requirements is called Requirements Engineering. It involves two main activities:

- Elicitation: Gathering requirements directly from stakeholders and other sources.

- Elaboration: Analysing the elicited requirements to derive other functions that are logically necessary for the system to work, even if they were not explicitly stated.

Once requirements are defined, we must ensure we build the right system and build the system right. This is the job of Verification and Validation (V&V).

- Verification: “Did we build the system right?” This checks if the system complies with its design specifications.

- Validation: “Did we build the right system?” This checks if the system actually meets the original stakeholder needs.

A system can be perfectly verified but fail validation if it was built to flawed requirements.

Finally, traceability is the thread that connects everything. It is the ability to follow a requirement’s life from its origin to its implementation.

- Forward traceability ensures every high-level requirement is addressed in the final design.

- Backward traceability ensures every design feature can be traced back to an authorised requirement. This is the primary defence against ‘requirements creep’—the addition of unrequested features that add cost and complexity.

Final thoughts

Working through these concepts has given me a much clearer picture of systems engineering. It is a discipline dedicated to managing complexity. By taking a structured, top-down approach that considers the entire life cycle, it provides a framework for translating abstract business needs into a successful, operational system. The emphasis on getting the requirements right from the start is a lesson that applies far beyond just large-scale engineering projects.