Beyond the vibe: structuring AI-assisted development

I recently came across a very informative post by Diwank Singh titled “Field Notes From Shipping Real Code With Claude”. It explores the concept of “vibe coding”—letting an AI assistant like Claude handle much of the implementation while the developer guides the process.

While the term sounds casual, Diwank’s article makes a crucial point: to make this work effectively in a professional environment, you need structure, discipline, and clear guardrails. It is not about mindlessly accepting AI output; it is about amplifying your own capabilities.

Instead of crafting every line, you’re reviewing, refining, directing. But—and this cannot be overstated—you remain the architect. Claude is your intern with encyclopedic knowledge but zero context about your specific system, your users, your business logic.

This post summarises some of the key ideas from the article and adds my own reflections on how these practices change our ways of working.

The different modes of vibe coding

Diwank’s article outlines three distinct modes of working with an AI, each with its own purpose and level of rigour. I have found this framework very useful for thinking about when and how to apply these tools.

| Mode | Characteristics | Best For |

|---|---|---|

| The Playground | Chaotic and fast. The AI writes 80-90% of the code with minimal guidance. | Weekend hacks, proofs-of-concept, and personal scripts. Not for production. |

| Pair Programming | Structured collaboration. The developer provides context and guidance, often through a project “rulebook”. | Small to medium-sized projects, well-scoped features, and side projects with real users. |

| Production Scale | Highly orchestrated. Requires deep context, strict boundaries, and careful integration into complex systems. | Large, mature codebases and monorepos where mistakes have significant consequences. |

The constitution for your code

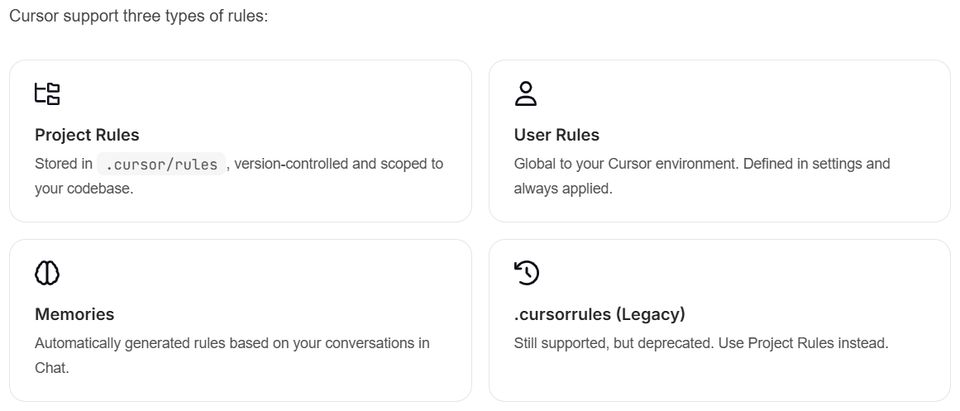

The concept of a “rulebook” is becoming a standard for professional AI-assisted development. Claude, Cline, and Cursor each offer a way to provide persistent context, but they differ in their approach. Claude’s CLAUDE.md is the most straightforward, while Cline offers more organisation with its folder system. Cursor provides the most granular and controlling system, allowing developers to define precisely how and when a rule should apply.

| Feature | Claude (CLAUDE.md) | Cline (cline.rules) | Cursor (.cursor/rules) |

|---|---|---|---|

| File Location | CLAUDE.md in repo root, sub-directories, or home folder. | .clinerules/ folder in project root or a global folder. | .cursor/rules/ folder, which can be nested in sub-directories. |

| File Format | Plain Markdown (.md). | Plain Markdown (.md). | Markdown with metadata (.mdc). |

| Activation | Automatic, based on file location. Always on if present. | Automatic (all files in folder are active) with a UI to toggle rules during a session. | Highly configurable: Always, Auto Attached (by file path), Agent Requested, or Manual. |

| Scoping | Repository, sub-directory, and global user level. | Workspace and global user level. | Project, nested sub-directory, global user level, and automatic “Memories”. |

| Key Differentiator | Simplicity and being unopinionated. | Organised folder structure and an easy-to-use UI toggle. | Fine-grained control and conditional activation logic. |

Applying the rules: the art of steering

However, as Diwank Singh’s article masterfully illustrates, the real power is not just in having a rulebook, but in the art of actively steering the AI. He details a layered approach that goes far beyond a single file, creating a hierarchy of influence from global principles down to task-specific directives.

Here are some of the steering mechanisms he describes:

- Anchor comments: These are hyper-localised instructions embedded directly in the code to act as surgical constraints. They bind rules to specific code blocks, reference architectural decisions, and use imperative language to override generic assumptions.

- Prompt engineering as control flow: This involves treating prompts as execution blueprints rather than simple requests. An advanced prompt hardwires business constraints, links to authoritative documents to reduce hallucination, and is designed to be token-aware to avoid iterative fixes.

- Workflow choreography: Instead of asking for code directly, the AI is orchestrated through distinct phases: research, planning, execution, and validation. This forces the AI into a structured problem-solving process that mirrors a standard software development lifecycle.

- Tool lockdown via permissions: This technique involves controlling the AI’s capabilities on a per-session or global basis, granting only the permissions absolutely needed for a task. It treats the AI like a least-privilege system process.

- Session psychology management: The article advocates for using fresh, task-bound sessions for distinct tasks to avoid “context pollution,” where information from a previous, unrelated task bleeds into the AI’s current model.

As Diwank summarises:

“Without proper guardrails, you’re playing whack-a-mole with an overeager intern. With them, you gain a tireless co-pilot who respects your flight plan.”

The sacred boundaries: what an AI must never touch

This brings us to the guardrails. While an AI can accelerate implementation, some areas of a codebase are too critical to delegate. The article provides a clear list:

- Test files: Tests are the executable specification of your intent. An AI should never write or modify them.

- Database migrations: These are often irreversible and carry a high risk of data loss.

- Security-critical code: Authentication, authorisation, and encryption logic must be handled with human oversight.

- API contracts: Changing an API can break client applications and should only be done deliberately.

- Configuration and secrets: The AI should never handle secrets or production settings.

The change in ways of working

Adopting these tools and practices fundamentally changes team dynamics and individual roles.

Onboarding a new developer, for instance, looks different. Their first task is no longer just setting up a development environment, but also reading and understanding the project’s rulebook. This document becomes the foundation for how they, and their AI partner, will contribute.

The role of a senior developer also evolves. As Diwank’s article highlights:

Your role as a senior engineer has fundamentally shifted. You’re no longer just writing code—you’re curating knowledge, setting boundaries, and teaching both humans and AI systems how to work effectively.

The senior developer shifts from being just a top producer of code to an architect of the system that produces code. Their expertise is now captured and scaled through the AI, guiding both junior developers and the model itself.

A reflection on software architecture

A final thought on software architecture: It might seem like these AI tools reduce the need for deep architectural thinking, but I think the opposite is true.

An AI cannot invent your system’s boundaries or understand the trade-offs behind your API contracts. It is a powerful implementation engine, but it needs a well-defined map to operate effectively. This forces us to be more explicit about our architectural decisions. The project rulebook is, in essence, a living architectural document that is both human-readable and machine-actionable.

With these new ways of working, the role of the software architect is still critical. Their job is to define the playground, set the rules, and draw the lines the AI must not cross. Vibe coding can be incredibly powerful, but only when it happens within a well-designed and clearly communicated structure.