Onboarding AI with READMEs and quality gates

In my last post on structuring AI-assisted development, I explored the idea of creating rulebooks to steer AI coding tools. While this is a powerful technique, I have sometimes struggled to get consistent, high-quality results from AI agents. The process can still feel like it requires constant supervision.

A recent article by Fuzzy Computer, “Onboarding for coding agents”, offers a practical solution that reframes the problem. Instead of focusing solely on instructing the AI, it proposes structuring the project environment so that the AI can self-correct. The core idea is simple but effective: use universal documentation for context and automated tools for constraints.

This approach creates a system that is not only beneficial for AI agents but also for any human developer joining the project.

The two pillars of the system

The article proposes a clear, two-part strategy for managing AI collaboration, moving away from tool-specific configuration files like CLAUDE.md or .cursor/rules towards a more universal setup.

1. Onboarding with READMEs

The first pillar is to treat every AI session like onboarding a new team member. Instead of putting project context into proprietary files, place it in a series of README.md files, a format every developer already understands.

Ask yourself: if a new software engineer or designer joined this project tomorrow, what would you want them to read before they start on their first task? That’s the type of context you should put in READMEs.

The article suggests a simple naming convention to keep this context modular:

README.md: The high-level project overview.README.architecture.md: Explains the application structure, data flow, and key patterns.README.commands.md: Lists key development scripts and commands.README.design.md: Details the design system and visual guidelines.README.testing.md: Outlines testing strategies and patterns.

This way, the CLAUDE.md file shrinks to a simple instruction list, telling the AI to read all relevant README files at the start of a session.

2. Quality gates

The second pillar is to enforce rules through the environment itself, not through text-based instructions. These are called “Quality Gates”—automated checks that must pass before the AI’s work is considered complete.

This works well because LLMs are terrible at formatting whitespace or sorting imports and Tailwind classes consistently, or ensuring every React hook’s dependency array is correct. But they’re good at running tools and fixing errors until all checks pass.

The article uses TypeScript as example, for a Python project we can make something similar:

ruff format .(Code formatting)ruff check .(Linting rules)mypy .(Static type checking)pytest(Unit and integration tests)

By instructing the AI to run these checks and fix any errors until they all pass, you delegate the tedious work to the machine while ensuring the output meets your project’s quality standards.

Giving the software an OODA loop

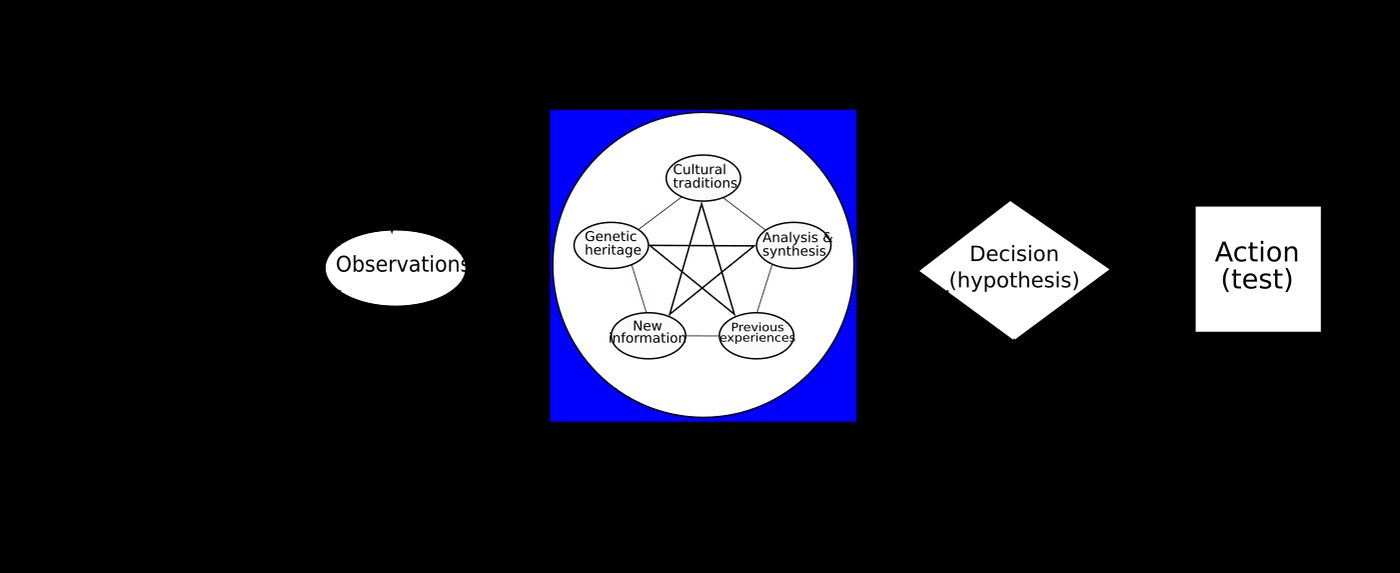

This “Quality Gates” pattern is effective because modern AI models can now operate in a feedback loop. The article connects this to the OODA loop, a decision-making model from military strategy.

Wikipedia describes the OODA loop as follows:

The OODA loop (observe, orient, decide, act) is a decision-making model developed by United States Air Force Colonel John Boyd. […] The approach explains how agility can overcome raw power in dealing with human opponents. An entity (whether an individual or an organization) that can process this cycle quickly, observing and reacting to unfolding events more rapidly and/or more effectively than an opponent, can thereby get inside the opponent’s decision cycle and gain the advantage.

When an AI agent writes code that fails a linting check (Observe), it analyses the error (Orient), determines a fix (Decide), and rewrites the code (Act). It repeats this cycle until all gates pass, effectively giving the development process its own primitive OODA loop.

An evolution of steering

This approach feels like a natural evolution from the concepts in my previous post. Where “vibe coding” with rulebooks is about actively steering the AI with prompts, this method is about building a self-correcting environment. It shifts the focus from micromanagement to system design. The developer defines the “laws of physics”—the tech stack, architecture, and quality standards—and the AI operates within that well-defined world.

I plan to implement this system in my own projects. The dual benefit is what makes it so appealing: it creates clear, modular documentation that serves both human developers and our new AI assistants, making the entire development process more robust and efficient.